A young girl, I’m in a car, driving from Florida to Montana with my family because my mom and dad decided to move out west. I’ve been counting fence posts, sulking because I’m unhappy about leaving my birth state of Florida. I’ll miss my friends, the ocean, the beaches, the smell of Coppertone sunscreen, the tennis courts… I’m wondering if I’ll be able to make new friends when I spot an old, weathered cabin sitting out in the middle of one of the prairies, a solitary sentry to the waving grasses. Purple and blue mountains rise up in the distance.

“Who lived in that?” I ask.

My father thinks for a moment, then says, “A little girl did. She raised her own cattle and collected her own water.”

“She grew her own vegetables,” my mom chimes in. “Lettuce, cabbage, zucchini…”

They’re joking, of course, trying to make a point that I have it very good by comparison. Which I do. And so do my brothers, who also chime in and start talking about the perfect prairie daughter and all she’s capable of.

When we’re done carrying on about her, she stays with me. I picture her. She’s unfathomably strong and capable. Her skin the color of pecans from the sun and wind. Her hands rough from carrying water and mending the garden. Her muscles already fully formed and sinewy like an Olympic athlete. I am in awe of her abilities to survive among elk and bear and broken fence lines.

But my mind snags onto something else, too: that so quickly after crossing the border from Wyoming’s northwest tip into Montana, with its famous big sky overhead, it’s sparking all our imaginations to life.

I wonder if I’ll like Montana.

I am in my late teens. At this point I have lived in northwestern Montana for five years. I still miss the ocean and the Florida beaches, but I have made new friends close to our new home.

I’m hiking with one of them up Gunsight Pass in Glacier National Park. The early-morning golden light smolders dramatically on the mountaintops, beckoning me to come take part in the day’s unfolding.

Glistening water from spring melt-off runs in rivulets down giant gray slabs of granite and wine-colored cliffs, creating a shimmering kaleidoscope of color. Serrated peaks tower above.

After we summit the pass and devour the lunch we packed, we begin our descent to Lake Ellen Wilson, a cobalt lake surrounded by jagged cliffs, sharp as razors against the sky. A flowery gentler mountain slope forms a meadow bursting with color. Pasque blossoms, bright-red Indian paintbrush, tall beargrass, and lemon-yellow glacier lilies spread out before me like they’re flirting, drawing us in.

As we zigzag down the narrow shale trail, I see a silver-brown blob moving among the wildflowers. I stop and focus. It’s a grizzly. Excitement and nervousness bubble. I nudge my friend and point. She pulls out her bear spray, a large canister of capsaicin used to stop grizzlies in their tracks if they charge. Luckily, we’re far enough away to simply observe him. He’s one of many grizzlies I’ll come across in my life in Montana, each time as thrilling as the first.

Hiking in grizzly country is exhilarating because it feels existential, as if you’re right at the edge of civilization.

We watch the bear’s sheer strength as it saunters across the terrain, occasionally stopping to turn over a rock or two as it looks for tasty roots to nibble. Its majestic hump protrudes like a warning, while the breeze pushes its long, thick fur around in waves across its muscular neck and back. White, fluffy Dr. Seuss-style beargrass, with its bulbous tops, surrounds him. Behind him, the ridgeline rises like a great wave. He turns and shows us his scooped silver face. I have the sensation that I’m living in a dreamscape.

Montana overwhelms me.

I am in my 20s. My boyfriend and I are hunting pheasants on the east side of the Continental Divide. I am not a hunter. I do not like to shoot things, but I agree to go along because I want to see more of this part of Montana. I’d been to several eastern towns for high-school sports, but I hadn’t really experienced the landscape other than through bus windows.

Eastern Montana is like a completely different state: the landscape, the dinosaur digs, the small towns, the Missouri River and its breaks, the endless array of migratory and water birds.

And the moon. When we headed over the Divide the evening before, a harvest moon hung low and orange on the eastern horizon. It appeared much larger and further away than it does in the Flathead, where it’s seemingly nestled in a cup by the mountains.

Now, we’re on one of the many Hutterite colonies in Montana. The Hutterites, an Amish-like community practicing an old-fashioned communal way of life, have given my boyfriend permission to hunt their thousands of acres. The Sweet Grass Hills stand guard in the north, not far from the Canadian border, rising to almost 7,000 feet (2,134 m) from pancake-flat prairies turned gold from farmers’ wheat and what’s left of the original silky, fragrant sweet grasses. In days past, roaming buffalo hooves would cultivate the grass by turning the soil and spreading the seeds, but without the presence of the great beasts, much of the grassland has been lost.

We walk through coulees, weaving our way up and down as we follow cattle and mule deer trails. Prickly brush hits our legs and I’m happy to have borrowed a pair of my boyfriend’s brush pants that I’ve cinched up with a belt so they don’t fall off. When the first pheasant breaks from the brush with a loud whoosh, my heartbeat skyrockets. My boyfriend’s gun fires. Green head, white-ringed neck, and spotted gold feathers plummet. The smell of nitro fills my nose.

Brisk gusts push the wild grasses around and freeze my cheeks. The setting sun casts a pink light across the Sweet Grass Hills that sprout from the vast windswept fields toward the colossal sky, indifferent to the closing of another day. Time unspools and folds in on itself around me. I sense it in the soil, in the grass, in the waving brush surrounding me for miles and miles. I feel very alone. I think of that falling bird—gold wings suddenly drooping; a swirl of red, green, white, and gold tumbling, falling, plopping hard on the ground. Its heart stopping.

Montana reduces me to a speck of dust.

I am in my 30s, “skiing by braille,” as we say in northwest Montana, where the winters are foggy and bluebird ski days are much fewer than socked-in ski days. I have been teaching all week at the community college in the valley and am looking forward to skiing with my son this weekend, thick fog or not.

Mist settles upon the mountain, blanketing the resort. Between the rime that has coated my goggles and the viscous fog, I can barely see more than three feet (0.9 m) in front of me. But I ski now like I was born in the mountains. I relish the sensation of my skis gliding through light, fluffy powder. If you ski, you know.

In the trees, the visibility is better. The pines provide landmarks, places to adjust your eyes and grab your bearings. Ice and snow build on the trees near the summit of the mountain in a way unique to northwest Montana, creating what we call snow ghosts. The ghosts, fluffy and elegant, are anything but soft. They’re created by the same rime coating my goggles as the fog that slinks in from the ridges brings in moisture, its liquid binding to the trees with coat after coat of ice.

But because perception is better in the forested areas on this foggy day, my son and I decide to go off-piste. We have a buddy system where we stay together, but he’s getting older, more independent. Within seconds of diving down into the trees, he’s off, gracefully weaving through the pines and out of sight. Out of calling range, too. I yell, but he doesn’t answer. My heart races.

But, when I do reach the lift, he’s waiting, a guilty look on his face. Relief floods over me. I have words with him, but the fog is now clearing. The clouds have parted, too, and a slice of cerulean heaven hangs above. The sun picks up the moisture left over in the air from the fog, making tiny crystals scintillate in the cold surrounding air. White, snow-frosted ridges hem us in, making us feel like we’re in a magical globe.

The stark beauty is stunning, intoxicating. We smile at each other.

Sometimes Montana frightens me.

I am in my 50s. I look out of my window from my desk. It’s early morning and a herd of elk is making its way through my backyard to go to higher elevations for the day. Cow calls ping through the silent morning, reedy but pure.

The night before, two mountain lions crossed outside our front door. Gorgeous, stealthy creatures passing through the night. We kept the dogs in and went out with them when we got up for the day in case the lions were still lurking. I watch the elk in the brightening dawn and hope they stay safe, but I know the cougars are out there, too, looking to cull the herd of its weakest links. My dogs come back proud with deer bones in their mouths more frequently than I’d like on our daily walks.

Sometimes I think about what my life would be like if I’d moved to a big city—if I’d had plays, museums, excellent restaurants, and all the other opportunities an urban lifestyle can bring. But then I think back on the recent anniversary dinner my husband and I had after spending a day in the Lamar Valley in Yellowstone National Park watching wolves. We dined in a grand lodge in Paradise Valley looking out at Emigrant Peak, with crisp white tablecloths, a creative cocktail menu, a fine wine selection, and food prepared by a world-class chef who’s come to Montana for the same reasons so many others seek it out: its beauty and simple lifestyle.

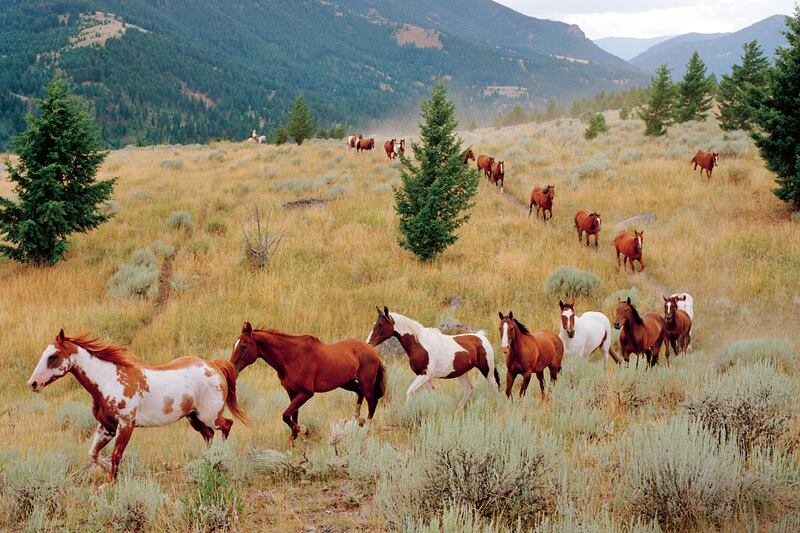

I’m rooted in the sights of cowboys silently brushing chestnut-colored horses beside old majestic barns, Indigenous Americans performing traditional dances with their colorful, feathery regalia, and fly-fishermen casting their lines at dusk in glittering water. I’ve seen fierce wind blow waterfalls toward the sky, ice crystals shimmering in the sun over frozen lakes, and grizzlies standing their ground, daring me to take another step in their direction. I’ve seen great horned owls perched in papery cottonwoods, elk locking antlers, mountain goats skipping across cliffsides, and bald eagles swirling as they perform dramatic courtship dances, all against the backdrop of a stark countryside that lets us know through its own language that we, too, are part of the Earth.

In Montana, I learn that strength comes from meeting the wild on my own and that finding solitude is not the same as escaping. Here, I’m in awe of how everything works, how from every minuscule bug to every massive moose, every living organism has a place and a function. Montana writes its own poetry with each sharp winter morning and every still summer night, indifferent to how often you pay attention, yet intensely welcoming when you do.

Montana has become my home. It can be cruel and unflinching sometimes, but there is an alluring gentleness in the sway of the land and in the buttery fall light. Montana has a way of burrowing itself deep into the souls of those who stay here long enough, the stark landscape rounding and sharpening their edges simultaneously, creating the effect of authenticity.

I’ve come from wondering about an imaginary little girl in a cabin forging her own home to forming my own. And, just like my folks did that day so long ago, I also create my own fiction, which is mostly set in northwest Montana. The stunning, vast state informs every bit of who I am, who I’ve become, and certainly my crime-fiction novels, too. All of my characters rely on Montana’s landscape to shape them as they react not only to rural society, but to the wilds surrounding them.

I inhabit Montana… but ultimately, Montana lives in me.

Writer’s bio: Christine Carbo is an award-winning suspense author of The Wild Inside, Mortal Fall, The Weight of Night, and A Sharp Solitude